What is the future of OPEX in Pharma? We look back at our series of publications in Pharma Focus Asia and provide an overview of how OPEX evolved in the industry during the past decades. Moreover, we suggest four propositions of future pathways of OPEX in Pharma.

In our previous articles we addressed several approaches and concepts which we either identified or developed to contribute to the advancement of the pharmaceutical industry. Thereby, we always used a combination of a research and practice driven perspective highlighting some key findings and patterns, which we have seen over the years. First, in our article The Link between Plant Performance & Maturity – Seeing the whole picture, we draw the attention to the fact that true performance cannot be measured with isolated metrics. Thus, we exposed the importance of jointly analysing performance together with the maturity of pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities. We further argue that on the one hand performance needs to be interpreted as an outcome measure related to effectiveness and efficiency but on the other hand maturity needs to be considered to build capabilities that lead to achieving higher effectiveness and efficiency. In our second article, St.Gallen OPEX Benchmarking for Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Sites - Measure yourself against the best but do it right, we further presented the St.Gallen OPEX Benchmarking as a solution to holistically assess a site’s performance. Since 2003, we provide insights to pharmaceutical companies by locating them in their competitive landscape and allowing for meaningful comparison. Drawing on the world’s second largest pharmaceutical OPEX-databases with more than 400 sites, we help to identify areas of improvement and further contribute to enhance the pharmaceutical industry. In our third article Benchmarking Pharmaceutical Quality Control Labs – Holistic assessment of Operational Excellence in Pharmaceutical Companies, we indicated that through the years more and more pharmaceutical companies have managed to extend OPEX and Lean-thinking beyond manufacturing. Nevertheless, we have identified that many pharmaceutical companies are still lagging behind when incorporating an end-to-end perspective. Especially the critical position of Quality Control (QC) labs in the pharmaceutical value chain is often times still underestimated. To address this gap, we developed the St.Gallen QC Lab Benchmarking, which takes into consideration the specifics of QC labs. With more than 130 pharmaceutical QC labs included in the St.Gallen QC Lab Benchmarking database, we apply a holistic perspective of performance and maturity to assess Productivity, Quality, Service and Cost as well as Enablers. In our last article, Learn from your Metrics – Using Operational Data to Improve Operations in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing and QC Labs, we showed how St.Gallen’s holistic approach on measuring performance allows companies to strategically define improvement initiatives that lead to stable and long-lasting enhancement of a company’s performance. Thus, we gave two distinct examples of improvement initiatives which were derived from St.Gallen benchmarking data. In this concluding article, we will take a look at the history of OPEX in the pharmaceutical industry and present our interpretation of the future.

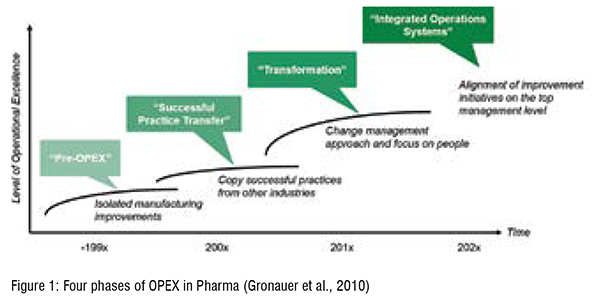

Compared to other industries the pharmaceutical industry was a laggard in adapting an OPEX philosophy and striving for continuous improvement. OPEX developed in three major phases (see Figure 1). As of the late 1990s, there were no structured and carefully designed approaches for improving manufacturing processes during the pre-OPEX phase. Moreover, the industry was characterised by a culture of "no change”. During the second phase, OPEX gained momentum and became a priority of Top Management and workforce (Friedli & Werani, 2013). This trend was not only a result of increased pressure on drug prices or the often-cited productivity crisis in pharmaceutical research & development, but was also mainly driven by regulators. Thus, it was the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002, which announced the pharmaceutical current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) for the 21st Century initiative. The FDA encouraged the pharmaceutical industry to adopt modern and innovative manufacturing technologies to improve quality, performance, and patient security (FDA, 2004). Thereby lean thinking and OPEX was not only considered a suitable instrument to improve operations but also to meet regulatory expectations (Friedli & Bellm, 2013). However, during that phase, the whole industry tried to copy successful practices from Volkswagen, BMW, Daimler and co with moderate success. Many companies initiated Six Sigma programmes and built extensive problem-solving capabilities, resulting in a wave of belt certifications. Yet, after certifications continued lasting improvements remained limited. By trying to transfer OPEX practices to pharmaceutical production by just copying training programmes wasn't enough to get employee buy-in. That is why the focus on people and change management constitute the third phase, the transformation phase. Most pharmaceutical companies appear to be in this phase, as they have overcome initial beliefs that success could arise from copying training plans, methods and tools. For most of the companies we work with, their OPEX programmes have now a significant focus on soft skills and more human related practices (e.g., empowerment of workers, teamwork, management involvement, coaching). In one example, the company moved away from all the different technical tools but focused on the basics of standardisation, problem-solving, and coaching, all aiming at encouraging employees to continuously improve. As we move forward, the "Integrated Operating System" phase is beginning to emerge. In this phase preventive and reactive OPEX will arise on the one hand and on the other hand, all improvement initiatives will be aligned at the topmanagement level (Friedli & Werani, 2013). Few examples show early advancements of OPEX programmes starting from the very top and comprising more than “just” production. (Figure 1)

To predict the “future” of operational excellence in Pharma, we suggest several propositions by looking at the past and how OPEX programmes evolved throughout the industry. Our research projects and exchange groups give us nourish ground to see what will (or might) happen.

As we outlined above, OPEX programmes in pharma did not just come about over night as they are. Over the years, their inherited nature has changed. This is not only true for the industry in general but also for specific companies. Take for example Toyota, the pioneer of lean. Its Toyota Production System was a result from years and decades of experimenting and learning (Holweg, 2007). By acknowledging the dynamics of OPEX programmes, companies will understand that they are not “done” with the sole implementation of certain practices. That is, OPEX programmes are not binary – having one or not having one. Instead, companies need to look after them if they are still on track and check how the execution is going, over and over again (Liker, 2017). Hence, today’s OPEX programmes will most likely not be the same in the future. Yet, how much they differ remains an open question. The following propositions might, to some degree, impact the evolution of them.

FDA’s Quality Metrics initiative with its draft guidance (FDA, 2015) and revised draft guidance (FDA, 2016) has recently gained new traction. A public docket open for feedback form industry and other stakeholders provides insights into the agency’s current thinking on reporting metrics to improve quality oversight (FDA, 2022). It moves away from solely asking for three metrics to suggest four broader reporting categories. In addition, the Office of Pharmaceutical Quality (OPQ) published a white paper on quality management maturity (OPQ, 2022). The agency perceives quality management maturity as “the state attained by having consistent, reliable, and robust business processes to achieve quality objectives and robust business and promote continual improvement.” (OPQ, 2022, p. 3) As regulators’ thinking goes far beyond sole compliance but aiming for a state in which improvements are the norm and not exception, OPEX is not the opponent but driver of it. That is, OPEX programmes and quality management systems that have in the past been viewed separately – are two sides of the same coin. The future should, and will, show more integration and alignment of both. Trends in deviations posing new improvement projects, taking every single event as an opportunity for improvement instead of just closing it, aiming for excellence in quality control and assurance, are just a few examples.

Another strong trend which we acknowledge through the years when exchanging with the industry is an ongoing and notable rising interest in the field of digitalisation. Pharmaceutical companies have long since recognised the opportunities of digitalisation to enhance OPEX initiatives. Human error reduction, quicker decision making, fast and transparent information cascades, ownership reinforcement and clear boundaries are expected benefits just to mention a few expectations. We see that more and more pharmaceutical companies have understood the concepts of Lean and OPEX and thereby consistently agree that digitalisation will neither replace human decision making nor the people at the shopfloor. Additionally, we cannot see that there will be companies that intentionally try to digitise waste and bad processes just for the sake of digitalisation. However, a potential threat is still given as more and more companies currently develop their digitalisation roadmaps and heavily invest in the field. The central question here is and will be how to align digitalisation efforts and OPEX and how do companies have to organise for change to integrate digital with OPEX.

For many years, OPEX programmes, their tools and improvements projects, have been perceived as a shopfloor-only topic. While it is arguably its origin, companies have moved beyond the shopfloor level up the organisational ladder. Several concepts are now applied to higher management levels and vertical integration increases. This in turn leads to OPEX programmes being more than just a toolbox which is adopted and adapted by sites. Instead, especially corporate OPEX teams are almost like network managers. They need to develop and align site individual roadmaps, monitor and track sites’ progress of implementation and decide on the right levers to pull as sites have different circumstances and goals. Thereby, sites might even take different roles such as “teaching sites” for the deployment of OPEX programmes.

In this article, we summarised our series of publications in Pharma Focus Asia. OPEX, as a philosophy directing an organisation towards continuous improvement, should start with transparency and understanding its current situation (Friedli & Bellm, 2013). Only with that, the right conclusions can be derived and decisions are not based on gut feelings anymore. Thus, benchmarking is an essential part of OPEX. Moreover, we outline several (not exhaustive) future pathways of OPEX in Pharma. The common notion of it is a broader and more integrated understanding of OPEX. The era of a cost-cutting-only, meant for shopfloor-only understanding is over. Many companies have taken the right path and successfully embarked on their OPEX journey. Other have or will fail eventually.

Our future research activities will verify (or invalidate) our propositions and also provide new ones – striving for advancing state-of-the-art operational excellence in Pharma.

Literature