In pharmaceuticals, the strategic marketing process is typically a formal, structured process. Whilst this may be efficient, it is often ineffective at generating novel thinking and differentiated strategies. But it doesn’t have to be this way. By making the process a little messier – adding problems that aren’t normally considered, adding personnel who aren’t normally involved, setting objectives that aren’t normally considered – strategic leaders can stimulate innovative, counter-intuitive thinking. This article describes practical approaches to making your strategic planning process less tidy but more effective.

In any large life science company, strategic marketing planning is a carefully organised, timetabled and structured process. There are several good reasons for this: a systematised procedure is necessary to coordinate multiple, cross-functional activities; a clear methodology, in which every step is visible, is essential when justifying large investments; and the exceptional technical and commercial risks inherent in the life sciences industry can only be mitigated by a deliberate and rigorous process. But this regimented approach also has disadvantages. It often leads to tick-box behaviour, in which the goal is to fill-out templates rather than to add real value.

Mechanised processes encourage mechanised thinking, resulting in plans that look much the same from year to year. And tightly controlled processes also tend to drive out innovative ideas because adherence to the process is valued above the quality of the output. In practice, many executives find the annual strategic planning a laborious task with limited value. But strategic marketing planning needn’t be a robotic act that leads to unoriginal thinking and cookie-cutter strategies. In this article, I look at how the annual planning cycle can be shaken up so as to keep its strengths whilst avoiding its weaknesses.

The strategic marketing planning process is a cycle of four fundamental stages (see box 1, derived from the work of Professor Malcolm McDonald). All effective marketing processes include these four stages, even if they are sometimes implicit. And each of these four stages offers the opportunity to deliberately disorder the process to create better outcomes without losing the benefits of a systematic approach.

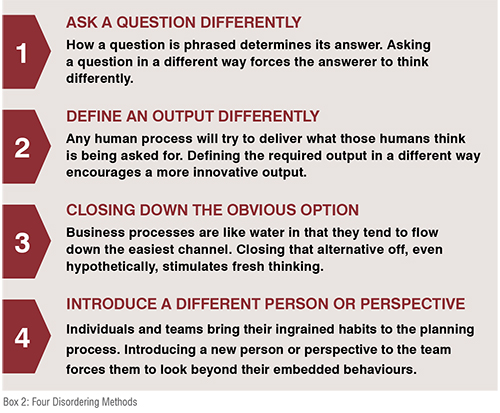

And there are also four basic approaches to disordering the marketing process (see box 2, which is inspired by Tim Harford’s excellent book, Messy). Each of these four disordering methods can be thoughtfully applied at any of the four stages of marketing, so offering plenty of opportunity to shake-up and re-invigorate your marketing plan. The following four examples illustrate how this disordering process works in practice, although this is far from an exhaustive list.

The first stage of the marketing process, understanding the market, is supposed to deliver the insight that goes into the second stage of strategic decision making. Too often, however, it creates nothing more than huge slide decks that do little more than repackage what is already known. Not only does this not help strategic thinking, it hinders it by burying people under data and causing ‘paralysis by analysis’.

This undesirable situation occurs because, when we ask for a situation analysis, the implied question is ‘what do we know about the market?’. If instead we rephrase that to ‘what do we know about the market that no one else does?’, it forces a search for true insight upon which competitive strategy can be built. For example, we might know a lot about the patient journey, the prescribers’ experience and the rates of non-adherence to medicines. But so, usually, do our competitors who buy the same market data from the same research agencies. But the challenge to find something only we know forces market analysts to look at the same data again and again until real insight, which is unique to us, emerges. For example, we might see that non-compliance occurs mostly at a certain stage in the patient journey as a result of a negative prescriber experience. This would be a genuine and strategically useful insight (See note at the end of article).

The second stage of the marketing cycle, making strategic decisions, is supposed to make and justify clear choices about where to focus resources, decisions which should create competitive advantage. and guide the third, implementation stage. Typically, though, the result is a blurred, indecisive compromise that fails to do either of those things. This results in scattergun tactics and, worse, a misplaced sense that there is a strategy when none exists.

This strategic muddle is the result of a semantic assumption. When we ask for a strategic decision, we assume that everyone knows and agrees what a strong marketing strategy looks like. This is very far from the truth. We can obviate that assumption by making clear exactly what we are expecting from the strategic decision process and this clarity forces the strategists to work harder. For example, we can make clear that the marketing strategy should take the format known as “Drucker’s Definition” and that it should score highly against the objective tests known of strategy diagnostics (See note at the end of article). This dare, to come up with a marketing strategy that is both clearly defined and objectively strong, encourages strategists to develop, test and reiterate their strategies until they have something better. For example, it demands a strategy that identifies the target market in terms of prescribing context, rather than simply the target patient or prescriber and strategy that offers a much stronger value proposition to that target, one based on both product and beyond-the-product value.

The third stage of marketing activity, implementation, is intended to identify and enact the operational and tactical activities that deliver value to the target segment or segments. But it is much more common that the implementation actions are little more than a reheated version of last year’s plan that have little impact on customer preference. This results in incomplete, incoherent and ineffective activities that not only consume resources but also have a high opportunity cost.

Implementation ineptitude is, in many cases, the result of inertia. Marketing teams spend what money they have become accustomed to, to do mostly what they have done before with methods and agencies with whom they are comfortable. This inertia is as powerful as it is invisible, but it can be broken by removing options that have traditionally been open to marketers. For example, we can request an activity plan that assumes there is no sales team or that congresses are not allowed or that the budget is halved. Even if these options are not, in reality, closed down and the budget not halved, the more constrained scenario forces people to think what they would do if they could not cut and paste last year’s plan. For example, it might force an honest reassessment of the role of sales people, the value of congresses and the return on marketing spend.

The final step in the loop of strategic marketing activities, measuring and learning, should do three things. It should test assumptions made during planning, provide information that guides strategy adjustments during execution and, after execution, tell us if the strategy has actually worked. In practice, marketing metrics usually give only limited, low-resolution information about what was sold, from which we can only indirectly infer some of these three things. This means that implementers have little chance to alter strategic course and each planning cycle is little better informed than the one before.

The inadequacy of marketing metrics has its origins in the perspective of the people who asked for those metrics. In most cases, metrics are demanded by leaders and finance colleagues who need to report upwards. And, since what they need to report is spending, sales and profit, then that is the focus of most marketing metrics. This situation can be improved by adding the perspective of other people in the organisation. For example, if we asked what the sales person, with her short-term focus, wants of metrics, we would develop metrics that predicted success in the immediate future and guided adaptation of the strategy during, not after, execution (so-called lead metrics). If we took the perspective of the strategists who have to write next year’s plan, we would develop metrics that tested and improved planning assumptions year on year (so-called learning metrics). Combined with traditional sales and profit data (examples of so-called lag metrics), these new perspectives would push marketers to develop so called 3L (lead, learning and lag) metrics (see footnote).

As these examples show, the deliberate disordering of the strategic marketing planning process can energise the lumbering behemoth of your annual planning cycle. But one can’t be reckless, because that would put at risk the benefits of a rigorous, clear and systematic process. It may well be necessary and desirable to inject some disorder into one or more of the four stages of the marketing cycle, but one should do so with care. Use the four approaches from box 2, but consider carefully how you do it. For example, defining the output differently risks being seen as ‘moving the goalposts’ and may be resisted by some marketers. Closing down options may be seen as Draconian, especially if it kills pet projects or threatens individuals’ status. As with any kind of change management, tread carefully and seek to gain commitment to, rather than impose, change.

The English word juggernaut is derived from Sanskrit and refers to an unstoppable force or heavy, lumbering vehicle. In many pharmaceutical and medical technology companies, juggernaut is a good description of the strategic planning process, with its inability to be flexible and original. There are good reasons for this rigidity, such as coordinating complex activity and managing risk, and like a heavy vehicle it would be naïve to expect the process to be nimble. But it is possible to improve your strategic planning process by the judicious, deliberate use of the four techniques described in the article (see box 2) at one or more stages of the marketing process (see box 1). Done deliberately, disordering your strategic marketing process can turbocharge your juggernaut.

Note: Readers who would like to know more about insight creation, Drucker’s Definition, strategy diagnostics, 3L metrics and other methodologies referred to in this article should read ‘Brand Therapy’ by Professor Brian D Smith, which is available on Amazon and all other book stores.