Drug assessment is now progressively taking sustainability criteria into account alongside traditional cost-effectiveness, for their procurement, pricing, and reimbursement policies for pharmaceuticals. Many pharma companies have effectively incorporated innovative actions in their production, consumption, and supply chain to improve environmental and social sustainability practices, and to address the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. In Europe, there is an increasing trend of the inclusion of environmental, social, and governance issues along with quality and pricing in the decision-making process specifically with respect to tenders and procurement.

To preserve a healthy environment and human well-being, there is a recognised need to move away from overconsumption, waste and ecological harm. Historical and current patterns of natural resource use are contributing towards negative impacts on human health and the environment. This is particularly evident in the global health supply chain, as the production of medicines, health products and equipment contain a high-level of an environmental and social trade-off impacts, and most notably in emerging markets.

Many products and materials that come into hospitals may be harmful to patients, staff, and those in the community. Some products may contain or release carcinogens, reproductive toxins, or other hazardous materials. Moreover, the healthcare supply chain contributes more than 70 per cent in greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, the healthcare sector is the second-largest user of energy and one of the largest users of water in large part due to goods and services purchased. Medicinal products and packaging are disposed after use, generating hazardous waste.

Healthcare organisations have the opportunity to minimise negative impacts resulting from their activity and to create positive, lasting impacts for their staff, patients, and community

In this regard, several concepts emerge in the corporate social responsibility strategy of healthcare institutions where sustainable procurement policies is a crucial part of an action plan, all of them related and with a common objective, such as circular economy strategies, net zero carbon emissions, the impact of pharmaceuticals on the environment and on antimicrobial resistances or the reduction of the use of plastic in healthcare.

Accordingly, sustainable procurement seeks alternatives that minimise human health and environmental impacts to support community health. The potential of green procurement as a policy instrument has been increasingly recognised, and over recent years there has been growing political commitment at national and international levels. It has been highlighted internationally by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and was established as a policy instrument within the EU in 2004.

In Europe, the European Commission and several European countries have developed guidance in this area, in the form of national green public procurement criteria. Depending on the level of ambition of public procurement authorities, procurement criteria can be classified as "core" (focusing on the key areas of environmental performance of a product) or "comprehensive" (criteria take into account more aspects or higher levels of environmental performance and go further in supporting environmental and innovation goals). Both core and comprehensive criteria set the minimum performance levels that products must fulfil.

However, in the procurement of drugs and medical devices, sustainable procurement is commonly known as environmentally preferable purchasing, which involves social and economic aspects as well. In sustainable procurement, healthcare organisations meet their needs for supplies and services while generating benefits for the institution, society, and the economy while minimising damage to health and the environment.

Medicines account for 25 per cent of emissions within the healthcare systems. However, a small number of medicines account for a large portion of the emissions, and currently there is a significant focus on two such groups – anaesthetic gases (2 per cent of emissions) and inhalers (3 per cent of emissions) – where emissions occur at the ‘point of use’. The remaining 20 per cent of emissions are primarily found in the manufacturing and freight inherent in the supply chain.

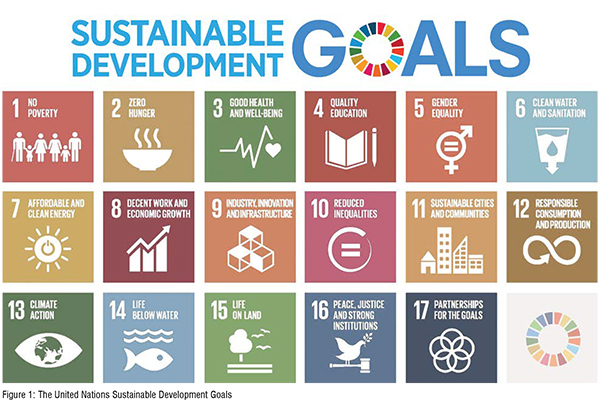

The international framework is the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which provide a blueprint for prosperity for people and the planet. Sustainable procurement addresses goal 12 on responsible consumption and production. Health care spending represents 10 per cent of the GDP in the OECD countries and almost 18 per cent of the U.S. GDP by 2030. Responsible consumption minimises the use of natural resources and toxic materials as well as emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle of the service or product. Sustainable procurement can leverage this purchasing power to help meet the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Figure 1:

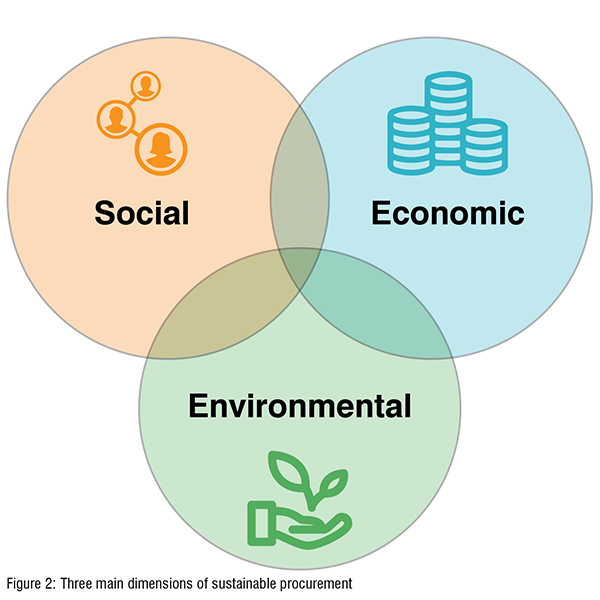

In everyday practice, according to The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, sustainable procurement refers a broad concept, embracing three main dimensions: environmental, economic, and social.

Every product has an ‘environmental footprint’ because of the energy and material resources used in its manufacture and delivery, as well as in its ongoing use and disposal. Product waste and its potentially toxic properties can undermine human health and the health of ecosystems. Hospitals and healthcare organisations have a significant role to play in promoting health by purchasing products and services that mitigate their environmental and health impacts on patients, staff, and surrounding communities. Some products contain carcinogens or reproductive toxics, some have outsized carbon and water footprints, and many are designed for single use and are excessively packaged generating a staggering amount of waste. Environmental considerations include reducing impacts on natural resources, air, and water; conserving energy; avoiding where possible chemicals of concern; and minimising end-of-use effects.

The economic aspect of sustainable procurement allows health systems to consider how their economic power can benefit all of society. For example, a health system can diversify supply chain vendors to promote economic wealth in underserved communities. Economic considerations include not only the purchase price of a good or service but also the total cost of ownership. Sustainability makes economic sense not only because it reduces inequalities across the value chain, but also because it supports financial sustainability. Valuebased drug procurement approach helps minimise costs, resources, and reduce inefficiencies.

The social dimension of procurement is concerned with the health and wellbeing of people while ensuring all partners in a supply chain uphold basic human rights in their employment and workplace practices. These rights are expressed in the International Labour Organization’s fundamental conventions and create a baseline for minimum standards in safe and healthy workplaces. Tools such as supplier codes of conduct help communicate expectations on human rights to suppliers. Figure 2:

In this regard, sustainable procurement is preventative medicine that supports a high-performance healing environment, attracts new opportunities, models leadership values to communities, patients and employees, and can save money to healthcare organisations.

The ultimate goal of bringing in sustainability into procurement is ensuring that a healthcare organisation makes more sustainable choices more often.

It is necessary not only to identify the sustainability criteria, but also to establish a necessary dialogue together between healthcare procurement organisations with drug suppliers and manufacturers. Defining the basis of the sustainability criteria can help both healthcare organisations and suppliers to use and fulfil these new requirements.

On the other hand, using a common set of criteria shared by other healthcare organisations tells suppliers there is a business case to produce sustainable products to meet market demand. It also guides suppliers on key issues in order to respond to requests for proposal or tenders with accurate data.

For procurers, using third-party labels and sustainability certifications can be an agile strategy to introduce sustainability criteria into procurement. Third-party labels are often voluntary initiatives demonstrating the environmental and sustainable qualities of products. Although many focus exclusively on environmental impacts, an increasing number include ethical and social standards that relate to decent working conditions, worker health and safety, and fair market return on labour. The International Standards Organization (ISO) classifies voluntary labelling into three types. However, ISO type I ecolabels are the strongest for procurement purposes because they consider all adverse environmental impacts of a product throughout its life cycle and are awarded only after an independent process of verification.

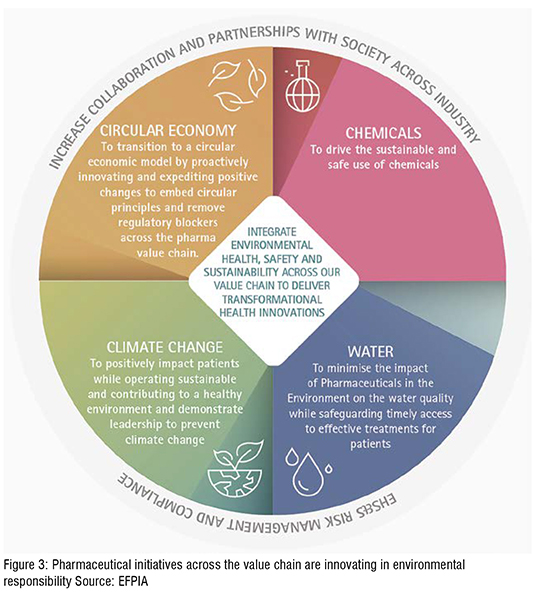

The pharmaceutical industry’s approach to circular economy builds on experience in sustainability, although the limitations, especially on speed of transition, from operating in a highly regulated industry. Due to the drug regulatory approval process, it is sometimes challenging to innovate in manufacturing processes or supply post-approval. The determination to move to a circular economy may also promote greater resource efficiency, create a more competitive economy, and reduce pollutants, but it needs to consider wider influences on the pharma industry activities, for example, on use of secondary materials in manufacturing.

Circular economy (‘circularity’) in the drug manufacturing process is based on a business model in which the manufacturer intends to maximise the lifetime of resources across value chains and reduce unnecessary waste and minimise environmental impacts, like climate change. Figure: 3

Manufacturing of pharmaceutical ingredients and products are strictly regulated to secure patient safety and quality through the principles and guidelines for Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). This apply irrespective of where the ingredient or product is manufactured. The environmental regulations governing manufacturing of products and APIs are, however, in general regional, national, or local. As the pharmaceutical industry is global, this consequently implies that environmental regulations in countries of manufacturing varies.

Environmental aspects may be included for pharmaceuticals procured as a healthcare policy, which can contribute to the development of environmental harmonised standards in drug manufacturing.

In December 2019, the European Green Deal for the EU and its citizens was launched, which aims to “making Europe climate neutral by 2050, boosting the economy through green technology, creating sustainable industry and transport, cutting pollution”. The Green Deal includes elements and initiatives that will or can have an influence on the environmental impacts along the pharmaceutical value chain, including climate impacts and emissions of APIs, as well as on the different identified applications to drive improvement along the chain, such as procurement.

Sustainable procurement should be lined up with the health organisation's sustainable responsibility goals, as well as with procurement priorities on drug selection and the formulary management, cost savings or patient safety.

Supplier engaging in sustainability can be undertaken with more powerful impact through procurement criteria. Engagement starts up communicating sustainable procurement strategy to suppliers and inviting them to work to achieve the organisation goals.

Sustainability value and benefits can also be tackled by a group procurement organisation (GPO), which have a significant role in advocating for sustainable procurement. Most GPOs have councils or committees that make recommendations and decisions on contracts. GPOs may also develop the elements of a sustainable procurement program, identify high-impact procurement opportunities, make recommendations on criteria, and support purchasing decisions to hospitals and healthcare organisations.

Assessing sustainable products and services available on the market that meet the primary function and technical requirements is also an action to be carried out by healthcare purchasers. This assess will have to consider misleading claims, ‘greenwashing,’ or harmful product substitutions.

Sustainability criteria consist of formulated requirements, together with motives for the requirements and suggestions for how to verify them. Examples of environmental criteria elements considered in drug tenders for drug procurement by the Consortium of Health and Social Care of Catalonia (Spain) are Environmental management, Ecodesign, Packaging (plastics and paper/ cardboard), Recyclable containers, Need for refrigeration, Emissions in the delivery and distribution of medicines and Waste management.

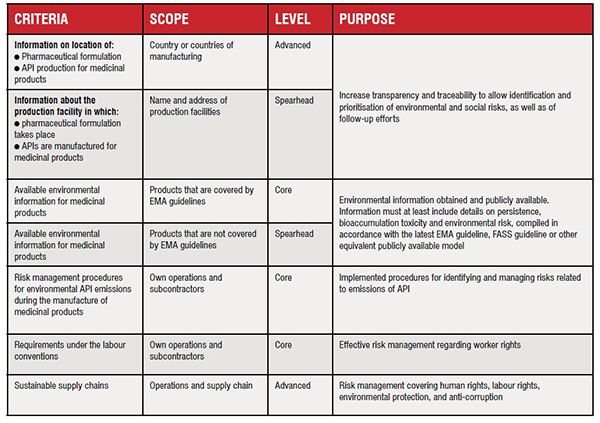

Sustainability criteria can be formulated as special contract terms or award criteria, and could be defined on three levels (Table 2):

a. Core level covers basic requirements focused on reducing most of the environmental/sustainability impact that is associated with the specific product area, which are more ambitious than applicable legislation

b. Advanced level goes beyond basic requirements. They may require more efforts in follow-up and verification for procurers

c. Spearhead level represents the best available alternatives in the market in terms of environmental and other sustainability aspects. They may require more specialised competence and efforts in work with follow-up and verification.

Procurement criteria are, however, voluntary for the contracting authorities to use. The implementation is made by the contracting entity who decides which criteria to include in the specific procurement situation depending on available information, resources, and ambitions.

In 2019, the EU presented a Strategic Approach to Pharmaceuticals in the Environment, which cover all stages of the life cycle of pharmaceuticals where improvements can be made. Although pharmaceutical policies have a higher impact on the development of a greener pharmacy, it should not be undertaken the deeper impact that decisions at the hospital level can have, as in the end, a critical decision-making point about medicines in the purchasing process.