Innovation in R&D requires both leadership and effective decision-making at the edges of our current understanding. Despite the advances in translational sciences, overall success rates are still low. In this article, we outline approaches to how decisions can be aligned across organisational and cultural boundaries, adapting to new information as it emerges.

Navigating the complex challenges of bringing new medicines to the marketplace requires both leadership and effective decision-making. New technologies and the development of translational sciences have created many new opportunities. However, the overall success rates are still low.

In this article we explore different approaches to decision-making and highlight the benefits of a distributed approach to support decision-making across organisational and cultural boundaries. We look at the structure of decision-making bodies throughout the process of bringing a new medicine to market, highlighting the dynamic nature of leadership and decision-making at the different stages of development. All of this is overlaid with the impact of the individual on the decisions taken.

In 2004, the FDA emphasised the importance of using translational science to understand the relationships between pharmacological action and clinical utility, safety and their potential as surrogate endpoints. In a recent analysis of the clinical development success rates from 2006-2015 in over 7000 projects, those that utilised patient selection biomarkers had a 3-fold better likelihood of approval from Phase 1 studies (1). Even in these cases, the overall success from phase 1 is still significantly less than evens. The sobering conclusion is that within the 9 years of focus on translational approaches, the most likely outcome of a drug discovery project is failure. However, there are areas to consider to help make appropriate decisions.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced machine learning techniques are becoming more popular and a number of companies use these approaches as a core business platform. The scope of activities ranges from de novo design to clinical trials and patient selection (2,3). Significant reductions in cost and cycle time are becoming evident with AI based approaches and it is likely they will become an invaluable resource (3).

The advances made over the last decade have supported decisionmaking in the pharmaceutical industry. However, other system effects have a consequence on the overall success rate of programs.

Developing a novel medicine requires working with a number of interrelated and distinct professional perspectives. Different medicine modalities such as chemical, biological or non-molecular entities have to be researched and evaluated with assessment of the likelihood of them being effective and safe. They need to be manufactured to specific control standards, gain access to appropriate markets and distributed to where they are needed.

It is perhaps not surprising that collaboration between these professional approaches improves success. For example, a study of drug discovery projects between 1991 and 2015 in leading US Academic Institutions demonstrated that collaboration with Industry resulted in higher probability of success, especially at the later stages of development (4). The ability to work effectively within an academic and industrial collaboration requires effort and skill from both partners.

A collaboration framework of 14 key principles has been developed to support an enabling environment to improve collaboration (5).

Elements of these have applicability for non-academic institutions. Perhaps one area to exemplify further is that of decision-making. Within the bio-pharma industry, multi-stakeholder collaborations often materialise through venture capital backed biotech companies that realise the value of academic innovation.

Biotech companies and related entrepreneur networks provide the vehicle for these collaboration principles. As the companies validate their technology and grow, many potential collaborations are identified, often attracting new partners.

The “what” we need to do and “why” we need to do it are often the focus for collaborative agreements. This outlines motivations and rewards associated with a variety of activities or tasks. With a high level of complexity and uncertainty in the development of new medicines, developing a framework for “how” decisions are made will be beneficial for all parties, especially in a multicultural context. Differences in cultural contexts such as individualism or collectivism can be managed effectively with clarity on “how” decisions will be made.

Clear roles in decision-making are important in all businesses. Many decision tools are available and a useful model outlined in 2006 in HBR magazine (6) suggests decisions involve various members of a team that provide input of data and a suggested course of action, agreement on the recommendation with input on various trade-offs before one person decides. The decision maker has several useful attributes including “good business judgement, grasp of relevant trade-offs, bias for action and a keen awareness of the organisation that will execute the decision”. This approach can be used to transform the performance of organisations at the team and/or organisational level.

However, within the complex, multistakeholder environment of a drug discovery programme the holistic and systemic nature of the business activities can be easily lost by breaking down decisions to a single decision maker. We offer an alternative approach, distributed decisionmaking that provides an opportunity to maintain alignment through various collaboration partners.

For the purposes of this article, we define distributed decision-making as a dynamic process that involves the right people at the right level, at the right time with the right authority to lead the decision-making process. Fundamental to its success is the recognition and facilitation of the interdependencies between peers across the network of decision makers.

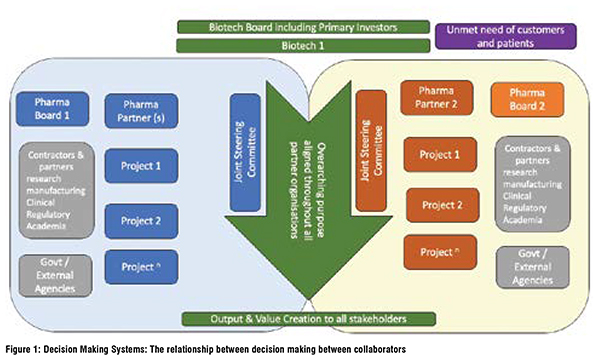

Figure 1 outlines the complex relationship between partners involved in the development of a new medicine from the perspective of a biopharmaceutical organisations; they may have many collaborations with smaller partners with a range of programs of activity across all stages of the drug discovery cycle.(Figure 1)

Irrespective of the stage of the activity, the overall goals of these organisations need close alignment to ensure delivery against objectives.

The Biotech board will include Executive, Non-Executive members and the primary investors. The overarching purpose and value proposition to satisfy the unmet need of customers and patients will be aligned through the various partners via a vehicle, often termed the joint steering committee (JSC). Typically, this is a decision-making body for all elements of each collaboration. It must align with the objectives of the Pharma Partner and their board. The activities of each Project will depend on a range of contractors, research, manufacturing and clinical partners, internal or external to the large company. As projects advance, there will also be Government and Regulatory considerations to align activities.

Representation on the JSC is for members of the Biotech and Pharma Organisation. Decision-making maybe by consensus or by vote (democratic) with escalation procedures in the case of non-agreement. One approach would be to have a 2-step process, the first step being mutual resolution provided by the appropriate CEO/Head of R&D and where necessary the second step of going to arbitration.

There are a number of enablers and disablers for decision-making

Good decisions are not vested in any one person. While command and control may have a place, effective decision-making will be dynamic involving a range of people, each of whom is able to offer a different perspective. This is most apparent when undertaking a major project that involves a range of disciplines, organisations and cultures.

Decision responsibility will be dynamic reflecting the stage and impact of the project.

The Biotech Board and Primary Investors will agree the purpose of the assignment and the involvement of others to secure that outcome.

The Biotech Project Board will have primary responsibility for the integrity of the project and for maintaining the agreed purpose and standards adopted by each subsidiary Steering Committee.

Each subsidiary Steering Committee will have oversight for their contribution and will manage the various decisionmaking groups ensuring that the right bodies and individuals are involved at the right time for the appropriate purpose.

Routine monitoring will be required to ensure that decisions taken by each of the Steering Committees to ensure they are aligned with the agreed remit and outcome.

Regular feedback will identify required modifications to the assignment whilst resisting mission creep.

Ultimate responsibility: Which body or individual role has ultimate responsibility for the decision? It is the role not the current occupant that carries this responsibility.

Crucial commitment: Which bodies or individual roles must be genuinely committed to the decisions reached? Without this commitment they will be able to undermine the decisions taken.

Vital contribution: Which individual roles have a responsibility to contribute essential information so that well informed decisions can be taken? These contributors will be unable to veto the decisions taken but can destabilise the process by withholding or distorting their information.

Decision impact: Which roles will be affected by decisions taken and must be made aware of those decisions.

Those involved in the decisionmaking process will change over time. Clarity around the roles of those involved in the process will avoid confusion and unnecessary competition and conflict.

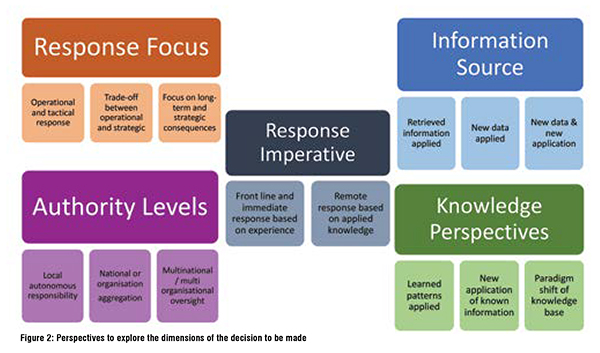

Distributed leadership and decision responsibility will change over time and incorporate a range of perspectives. Figure 2 details the spectrum and boundaries reflecting the needs of the decisions required. Each spectrum should be viewed as independent of the others.

Starting with the Response Imperative, a question to consider is “does the response need to be immediate, based on our current experience?” or is it more “remote, based on the application of our knowledge?”

Other perspectives to consider are the focus of the response, the authority needed for decision-making, consideration of the source of information and how knowledge is applied.

This approach also identifies the urgency and the organisational level of response. The next consideration, is the individuals involved in making the decision.

Decisions-makers require the essential technical knowledge and skills. It is no longer appropriate to involve a person because of their status or the fact that they have time on their hands. Those with the necessary knowledge, skills and experience are the people who can make the greatest contribution.

But over and above this is the impact of the individual. Each person has a unique thinking pattern that means they will concentrate on different aspects of the decision-making process.

If those involved in the decision-making process are focused on different stages, they will be less likely to reach a decision where there is a common understanding and where there is genuine commitment to implementation of the decisions taken.

A further complication is the fact that each person will have their own interaction needs at each of these three stages.

Neither is right or wrong; both have their strengths and weaknesses. The important thing is to recognise these patterns and to accommodate them in a way that makes decision-making as comprehensive and effective as possible.

Senior Leaders may also consider the development of the enablers of decisionmaking skills as an important part of the learning and development of both the individual and the organisation.

Shared responsibility for decisions increases ownership and is better able to maintain the focus on the overall purpose of the assignment.

No one person has the knowledge, skills, experience and ability to fully understand the trade-offs to be made; a decision that builds on the strengths of all those involved will be a more rounded and sustainable decision.

Identifying the roles and relationships will prevent decisions being taken on autopilot; assumptions will be challenged and a common platform agreed.

Thinking in terms of roles and responsibilities rather than named individuals will encourage objective and no-judgemental decisions and avoid the blame game.

Working in this way allows for greater agility and an ability to respond deliver under pressure without feeling under personal attack.

We have defined distributed decisionmaking as a dynamic process that involves the right people at the right level, at the right time with the right authority to lead the decision-making process. Fundamental to its success is the recognition and facilitation of the interdependencies between peers across the network of decision makers.

Maintaining alignment of purpose, process and people across a major multicultural project is complex and difficult.

The risks associated with such assignments can be reduced by introducing the monitoring and feedback routines to maintain an unerring focus on purpose and outcome that is robust and involves all players.

Risk is also reduced by understanding the dynamic nature of key decisionmakers and the contributions essential to secure success.

The overarching Steering Committee does not know all the answers, but has a responsibility to facilitate a decisionmaking process that secures ownership and genuine commitment to implementation of the decisions taken.

References:

1: Thomas et al., 2016. Biotechnology Innovation Organisation. https://www.bio.org/sites/default/files/legacy/bioorg/docs/Clinical%20Development%20Success%20Rates%202006-2015%20-%20BIO,%20Biomedtracker,%20Amplion%202016.pdf Accessed June 2022.

2: Elbadawi et al., 2021, Drug Discovery Today 26, 769-777 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2020.12.003,3: Paul et al., 2021 Drug Discovery Today 26 (1) 80-93 https:///doi.org/10.106/j.drudis2020.10.010

4: Takebe et al., 2018, Clin Transl Sci 2018 11, 597-606 https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12577

5: Awasthey et al., 2020 Journal of Industry-University Collaboration 2(1) 49-62 https://doi.org/10.1108/JIUC-09-2019-0016

6: Rogers &Blenko 2006 Harvard Business Review January https://hbr.org/2006/01/who-has-the-d-how-clear-decision-roles-enhance-organizational-performance