MODELLING SUCCESS

What is a business model, and how can you build one?

Brian Smith, Principal Advisor, PragMedic

In recent years, the term ‘Business Model’ has come to dominate board-room conversations. Whether firms want to adapt their existing business model or create an entirely new one, the term has become ubiquitous amongst pharma business leaders. But what is a business model? How does it differ from strategy, structure or revenue model? Ask 100 people for a definition, you will get 100 answers to the question. Such confusion and vagueness is the enemy of change management. In this article, Brian D Smith looks at the research into business models and gives us a new, practical and useful definition, based on his study of the industry, that helps pharma business leaders understand what a business model is and how to build one.

Is your market the same as it was five years ago? Has it been unaffected by the advance of medical science and information technology? Have changes in healthcare systems, demographics or economics made no difference to your business? Of course not. Every life sciences company is caught in a whirlwind of change that offers a stark choice between adaptation or extinction.

As companies from Roche to Merck demonstrate, successful adaptation begins with a shared vision of the future business model. But therein lies the problem. What is a business model? Despite it being peppered over every meeting and filling the media, there is no agreement amongst either academics or executives about the definition of this ubiquitous term. And, as the biblical story of the Tower of Babel tells us, there is no construction without clear communication.

In my research, which studies the Darwinian evolution of life sciences companies, the concept of business model is central and, in this article, my aim is to share that thinking with you. Stay with me to discover what a business model is and how you should build yours.

Lessons from nature

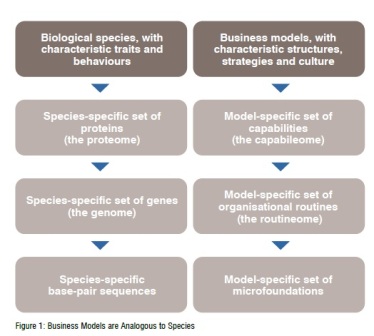

Although the metaphor can be stretched too far, business can draw many lessons from biology. A tropical rain forest, for example, supports a multitude of different creatures and this diversity is possible because evolution has led to speciation. In Amazonia, the sloth, the piranha and the jaguar survive not by competing with each other but by adapting to different habitats within the jungle and different niches within those habitats. Darwin observed how each species has different capabilities and is recognisable by distinctive traits and behaviours. He couldn’t know, as we now do, that those visible characteristics are the result of invisible, species-specific genomes and proteomes.

This conception of a species maps directly onto the definition business models. The thousands of companies in the in the life sciences ‘jungle’ are not identical but group into ‘species’ that we call business models. For example, Dr Reddy’s and Roche, although both pharmaceutical companies, do not look or behave the same. They do, however, share traits with the likes of Ranbaxy and Novartis. Even within large companies like Pfizer, the divisions for mature products, innovative products and rare diseases are not the same business model. Justlike biological species, business models have characteristic traitsand behaviours, such as strategies and structures. And just like species, these observable traits are the outward manifestation of internal properties. My work on uncovering this is summarised in figure 1.

In practical terms, this means that your business model is not unique to your company. A business model is a group of companies (or parts of companies) that share the same traits and behaviours, enabled by the same capabilities and routines. Viatris, Organon, Sandoz and Teva are all minor variants of the same business model, for example. And, if you study them internally, they share very similar capabilities and organisational routines. Importantly, both those visible and internal characteristics are different from, say, Fresenius, Baxter or Braun, who fall into another, very different, business model.

Speciation of business models

This equivalence between business models and biological species carries another important practical lesson for life science companies trying to adapt to the future. There is no such thing as the ‘best’ species. There are only species that are well adapted to their habitat within their environment. In the Amazon forest, sloths and piranhas each thrive in their place but wouldn’t survive in each other’s habitat. In exactly the same way, there are no ‘best’ or ‘worst’ life sciences business models, only models that are well- or poorly- adapted to their environment. A research-intensive business model like AstraZeneca may thrive when creating exceptional clinical value for seriously ill patients in advanced economies. It would, obviously, struggle to compete

in the habitat of providing generic small molecules to out-of-pocket patients in the world’s poorest companies.

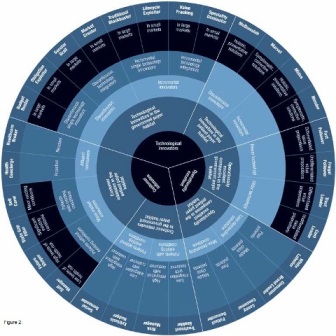

My research uncovers no fewer than 26 different life sciences business models (see figure 2). Each of these models has characteristic strategies, structures, cultures and other traits. They also have model-specific sets of capabilities (their capabileomes) that are the expression of their model-specific sets of organisational routines (their routineomes).

Does your model fit?

This conception of businessmodels-as-species is practically useful to life science leaders because it helps them answer two critically important questions: What should our business model be and how should we build it?

A firm’s choice of business model (business models in case of larger companies) is idiosyncratic. That is, it is a very individual choice driven by the firm’s past history, future goals and the trends shaping the market. The business-modelas- species concept helps leaders make this decision because it helps to identify their options. Also, by looking at other companies currently using the same model but in different markets or therapy areas, leaders can crystalise what their new model might look like. In practice, by considering the 26 models revealed in figure 2, leaders are forced to clarify the strategic choices involved in selecting a business model. If they fail to consider those choices, or if they fudge them, their company risks ‘straddling’–being adequate at many things but competitive at nothing.

How do you build it?

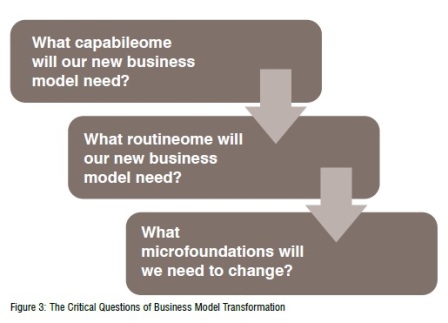

Choosing a business model is, of course, only the beginning. The real work lies in transforming your existing model into one that is better adapted to the future. In many cases, this transformation fails not because the new model was wrong but because the transformation effort was superficial. Leaders change names and move around the boxes on the organisation chart but without any substantial impact on the firm’s traits, behaviours or capabilities. To extend the biological metaphor, those leaders try to turn a chimpanzee into a human by training them to talk. But without the necessary genome and proteome, this transformation can’t be any more than superficial. The business-model-as-species concept helps leaders to effect genuine, substantial business model transformation by guiding them towards the three critical questions they must ask (see figure 3).

In most cases, business model transformation is an evolution, requiring incremental but carefully-considered change. For example, business models that involve small target markets require advanced capabilities in market segmentation Similarly, models that create value beyond the product require capabilities in extended and augmented value proposition design. Both of these capabilities require organisational routines that are not common in life science companies that target large markets. And engineering the routineome, just like engineering the genome, requires precise manipulation of its components, known as microfoundations.

Building microfoundations

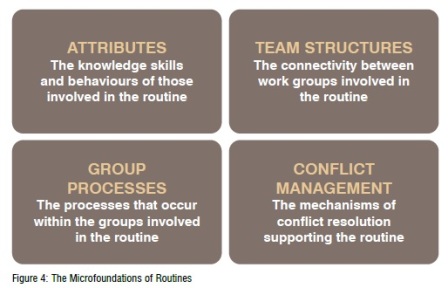

Creating new organisational routines that express themselves as new capabilities requires much more than a new process. New processes don’t work unless those involved make it work. In practice, this means developing the microfoundations of routines, as shown in figure 4.

What figure 4 reveals is that, to make a new organisational routine work effectively, it is necessary to think through the details. Are the people capable? Are the right sub-processes in place? Are teams connected appropriately? Are there mechanisms in place to avoid and resolve inevitable intraorganisational conflict? This process is as pain-staking as genetic engineering and it is no coincidence that the four types of microfoundations have the acronym ACTG.(see figure 4)

Modelling success

Not every life sciences company needs a new business model. Yours may be working well and not affected by the way the world is changing. But given the pace of social and technological change, most life sciences leaders need to review their present and future business models. To do so requires a clearunderstanding of what a business model is and the model-as-species idea helps them choose their future model and to make the transformation.