PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT

Adopting industry best practice requires three critical skills

Brian Smith, Principal Advisor, PragMedic

Many pharma industry executives think that success can be found in ‘best practice’ – imitating the behaviour of successful companies. Many consultancy companies make good business selling the idea of ‘best practice’ in business models, strategy or organisational structure. Yet the concept has no evidence base and runs counter to the idea that every firm is different and faces a different market situation. In this article, I’ll describe why the idea of ‘best practice’ is a myth and why the mantra ‘what works is what fits’ is the only one that acknowledges the realities of your firm’s uniqueness and your market’s characteristics. Using examples in from business model design, strategic planning processes and organisational structuring, it will explain how to address these challenges in a firm-specific way, avoiding the consultants’ cookie cutter.

Every life science company is eager to find and absorb industry best practices — and for good reason. In a business environment that is changing quickly, no firm can afford to be left behind and relying on internal experience and lessons is too slow. It is essential to imitate as well as to innovate. But, as any experienced business leader will tell you, assimilating the processes and methods of other firms, even apparently successful ones, is fraught with difficulty. The devil is in the detail of the differences between the exemplar and the emulator, and a transplant of best practice can often be rejected.

In my work, which focuses on how life science firms evolve in response to changes in their technological and sociological environment, the reasons for this failure resolve into three critically important lessons. In this article, I’ll illustrate them with examples, taken from my research, of three common attempts at embracing best practice.

Say exactly what you mean

Consider the case of a research-driven, primary care pharmaceutical company trying to adopt a new business model. Driven by intense competitive pressures on its current model, the firm looks around and sees a firm in a related market that is being successful with a service-led business model that creates most of its value – and its competitive advantage – 'beyond the pill’. Pushed by growth targets and pulled by envy of the exemplar company, our wouldbe emulator tries to copy the business model of its more successful peer.

But it fails. For reasons that it does not fully understand, its attempts at value beyond the pill don’t seem to impress its customers. Extra costs, associated with added-value services, do not achieve their intended return on investment. Competitive pressure intensifies and results do not improve.

There are many possible explanations for this failure, which has been repeated by a number of life science companies, but the obvious ones – incompetence or under-investment – are not usually supported by the facts. In this case, the emulator saw the visible aspects of the exemplar firm’s model – high levels of service – and imitated those very well.

Instead, it was matter of semantics. Our emulator’s leaders had to narrow a definition of the term 'business model’. This modish phrase is actually an umbrella term that includes strategy, structure, monetisation methods and other things. But by conflating the expression with only a narrow part of the value proposition, the emulator’s leaders forgot to pay attention to the other necessary parts of the model. So, they failed to target those market segments that valued – that is, would pay for – service, they failed to structure themselves for service delivery and they neglected to find a way to create revenue from service. All because of the way they defined 'business model’.

This failure, and others like it, would have been avoided if someone on the leadership team had asked a simple question: What exactly do we mean when we say 'business model’ and how is it different from other, related ideas like strategy? Amongst academics, who are taught and paid to think critically, this issue is known as'construct definition’. In plain English, it translates to a simple lesson that is critical to the successful adoption of best practice: When you use a term, say exactly what you mean.

Respect differences

For our second example, consider an in-vitro diagnostics company that is classed as 'small to medium’ but which, thanks to innovative and patented technology, is growing very rapidly. Faced with managing a larger business and flush with cash flow, the flourishing firm decides to invest in its strategic marketing capabilities. It picks one consultancy from the long line queuing up to take its money and commissions a 'Marketing Excellence’ programme. It is expensive but the consultancy can claim, honestly, that its strategic marketing planning process is based on that of one of the most successful large firms in the same industry. They truly do offer 'best practice’ in strategic marketing.

Again, the transplant fails. The new process is much more laborious than the one it has replaced. It absorbs a lot of time and effort but does not produce a significantly different output. True, the marketing department now produces some splendidly professional looking presentations. And there is a lot of new jargon, which sounds like that heard in the corridors of multinationals. But there is no real-world impact and, to a significant degree, the new jargon and process creates division between marketing and their colleagues in medical affairs, sales and other departments.

It is not always easy to explain the expensive failure of a process that was so successful elsewhere. Again, the obvious explanations can be ruled out; the importation had senior leadership endorsement, was supported by a very generous investment of time and money and the consultancy was world famous. Yet the project was a failure – expensive in both direct and opportunity costs – despite being best practice imported from the industry’s leading player.

But the failure can be explained. The strategic marketing planning process miscarried not despite its origins in a successful big company but because of those origins. By assuming that what works in one diagnostic company would work in another, the emulator’s leader ignored the reality that every firm is different from every other. In this case, the main difference lay in the nature of the markets that the strategic marketing planning process had to address. The large, exemplar firm operated across several related but very different submarkets within the in-vitro diagnostics sector. And each of those markets, being quite mature, had segmented into numerous different customer types. As a consequence, the exemplar firm needed and had developed a very complex and sophisticated strategic marketing planning process that exactly matched its needs. By contrast, our emulator firm was tightly focused on one sub-market of the in vitro diagnostics sector and that market, being relatively immature, was relatively homogenous and unsegmented. Although the complex, imported process could be applied to this simpler situation, it was not needed. It was, as one of the emulator’s leaders said to me, akin to buying a Ferrari to do the school run. It looked good but it was extravagant and unnecessary.

This failure to adopt best practice would have been avoided if the leadership team of the emulators had applied a critical test that is beaten into young academics. Is the success in one setting (in this case, the large, complex market of the exemplar) likely to happen in another setting (in this case, the simpler market of the emulator)? This piece of critical thinking – the test for external validity as my academic colleagues call it – would have made the emulator pause before signing a large cheque for the consultants. They would have reduced the risk of transplant rejection by looking for an exemplar from a smaller, simpler market. This provides a second lesson for those who would adopt best practice: When you import ideas from one context to another, respect the differences.

What works is what fits

For our third example, consider a speciality pharmaceutical company that wants to become 'patient-centric’. The firm can cite many rational reasons for this. Being customer-oriented has long been the mantra of every marketing professor. And the concept of customer-centricity fits well with the mission statements that hang on the wall in the firm’s reception area. But, if they are honest with themselves, the firm’s leaders are also influenced by the fashion for patientcentricity that is sweeping the industry. After all, as the emulating Chief Marketing Officer said to me, what are we centred on if not the patient?

In this case, failure was slower and less visible but none the less it became clear both externally and internally. In the market, relationships with important Key Opinion Leaders eroded. At the same time, payers complained that the firm’s commercial leaders were not listening to their needs. And it was noticeable that the firm’s value proposition to the market, formerly crystal-clear, became blurred. Internally, communications within brand teams between marketing and some of the more technical functions, such as market access and regulatory affairs, became strained. Team cohesion eroded.

Because the concept of patientcentricity seems so intuitively right, it was hard to understand why it was failing in practice. Obviously, the patients’ needs are important and obviously they should drive what the company does. And the company had manifested the concept in its goals, metrics, strategy and tactics. How could that be wrong?

This slow, imperceptible failure was not understood until a new leader arrived with fresh eyes and an interesting turn of phrase. 'What works is what fits’ she would say, in recognition that every initiative, process or strategy had to align with both the market’s needs and the firm’s own culture. In this case, patient centricity was not aligned to either. The patient was important but, in a market where they had little influence, success depended mostly on meeting the needs of the specialist physicians and the payers who had to justify the costs of the firm’s effective but costly products. Internally, the company had a culture, embedded over decades, of scientific prowess and excellence in understanding the disease and its treatment. That culture struggled to change priorities to include relatively nebulous, unscientific ideas such as the patient experience and non-clinical benefits. Patient-centricity did work in other contexts but, in this firms, was a doubly-misaligned to both the culture and the market.

This pernicious and slow failure would have been avoided had the new leader, with her characteristic chant, had arrived earlier. Rather than blindly adopting the new, fashionable idea of patient-centricity, the emulator firm might then have asked how it fit with the firm’s external market and internal culture. The influential academics Burrell and Morgan called this two-way fit idea 'bicongruence’ and saw it as essential to any business initiative. Translated from the academic, bicongruence is expressed as our third lesson of best practice adoption: What works is what fits.

Three lessons to learn

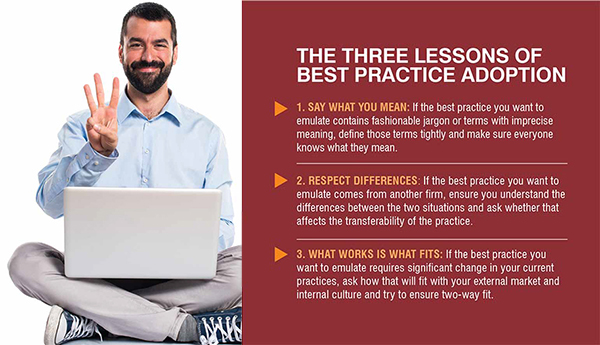

As these real, but disguised, examples show, the idea of adopting best practice is a good one. What life science firm, faced with rapid change, can afford not to borrow good ideas from elsewhere? But best practice is only valuable if it is chosen well and assimilated thoroughly. Firms who are good at this have learned three critical lessons (see box 1) that, unsurprisingly, have been observed by business academics like me and given fancy names. But whether you choose to use academic argot or plain language, these are critical lessons for leaders in the life sciences.