The pharmaceutical industry is facing a tough road ahead in the future marketplace. Though pharmaceuticals remain the most cost-effective healthcare intervention, they should bring about a significant transformation in their organisations to realise the glorious future.

One thing is for certain, today’s pharmaceutical marketplace is punctuated by change and uncertainty. The pharmaceutical industry is facing a tough road ahead in the future market place. Major products are facing patent expiry and pipelines are not replacing the ageing products. Approvals of NMEs continue to decline while development and commercialisation costs continue to skyrocket. While not entirely doom and gloom, many in the industry are faced with uncertainty on the future of their position in the marketplace and are left wondering what the future holds.

It is clear that there is increasing competitive pressure in the pharma industry and the breakneck rate of spending cannot continue ad infinitum. Pharmaceuticals remain the most cost-effective healthcare intervention and there will always be a market for good medicines. Many trends are currently adaptive and will continue, while others will need to be transformed. This transformation will require significant changes throughout pharmaceutical organisations.

The changing landscape of the pharmaceutical industry

The current state of the pharmaceutical industry is not good. IMS says that the US prescription drug sales growth is just 4 per cent. Wholesale prices grew by just 3.8 per cent which is the lowest increase since 1961. Just open up any recent news story and one will see companies making changes in response to the unfolding pressures in the industry. GlaxoSmithKline is set to cut down 12 per cent of its US sales force in a move to re-focus on therapeutic areas and respond to changing customer demands. Other companies like UCB, Pfizer, BMS etc. have also responded to the changes with layoffs.

Several key challenges are currently facing the industry:

Increasing public pressure

With an abundance of information, the health awareness among consumers is increasing at an exponential rate. They are demanding fair value and are constantly looking for greater value for the money they spend on medicine. For example, seniors under the US Government’s Medicare programme consistently prefer generic alternatives to branded drugs. They are astute shoppers who look for innovation. They expect pharma to tackle the tough diseases like diabetes, obesity, and cancers to name a few. They are growing increasingly impatient with incrementalism.

Increasing payer pressure

Similar to the society as a whole, payers are pushing for more innovation as they manage ever tightening budgets looking for increased health outcomes. The tougher cost-containment practices by payers are forcing pharma companies to bring forth innovation while at the same time providing disincentives for products with marginal benefits. It will be harder for me-too or me-better medicines to be successful. In most countries, payers are becoming even more active in determining which treatments are appropriate. For example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) can prevent a product from being used in the UK. Currently, even the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG) and the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) do not have that authority. Pricing transparency is increasing as well (formerly confidential contracting information is now becoming public).

Increasing patent expirations

It is forecasted that US$ 115 billion worth of branded drugs will become generic during the period 2007 through 2012. Numerous large blockbusters that are the backbone of the organisation’s top-line and more importantly profit are expected to be eroded by 2012 (e.g. Prevacid, Flomax, Lipitor, Crestor, Seroquel). To illustrate, Merck & Co. is expected to face generic competition from three of its top selling products (Fosamax, Singulair, and Cozaar)—which represent 44 per cent of the company’s revenues. This problem has only been exacerbated by the slowing degree of FDA approvals. In 2007, the FDA only approved 19 new products and is on track to have another record year of low approvals.

Decreased R&D output

The average cost to develop innovative therapies is skyrocketing. The average price of bringing a drug to market is now US$ 800 million. Due to the increasing costs, large pharma is increasingly turning to in-licensing to compensate for decreases in R&D production. Since 2002, in-licensing will increase from 17.5 to 34.4 per cent by 2012. If a company seeks to in-license later stage at the last minute (and hence reduce the risk), the law of supply and demand would govern and escalate the price level to a new height. When seeking to acquire new assets, it is also clear that the small molecules continue to be the target of choice (MAbs and therapeutic proteins being the preferred ones).

Increased focus by regulators on safety

While drug re-importation continues to be on the radar screen for many (including FDA), regulators continue to impress the need for safety in the development process. FDA mandates even greater number of patients to be used for clinical trials. Relatedly, they are looking for comparative safety of the New Chemical Entities (NCEs) to already marketed products. This has been even more manifest by the recent implementation by the FDA Amendments Act and the “Safety First” initiative.

Outsourcing

Clinical studies have long been outsourced as a more efficient way to get drugs to market. Contract manufacturing has also been around as a viable source (dating back into the early 1980s). In the 1990s, the outsourcing of the sales force became a popular decision in order to avoid the initial capital outlays and to have a more scalable solution. This is an ever growing popular trend as of late, and will no doubt expand into other commercial areas. Even more interesting are decisions to decouple once traditional mainstays of the organisation like HR, finance, and accounting. However, organisations haven’t stopped there as they are still pushing the envelope to extract value in innovative ways as evidenced by the Lilly/Chorus relationship. In essence, Lilly licenses the drug to Chorus and has the option to buy back after Phase II. This not only reduces the infrastructural needs of Lilly but also increases its productivity and capital efficiency. This will also have an impact on the time-to-market of their new products.

Successful transformation will require a cohesive strategy

Traditionally, working capital has not been a management issue for Big Pharma. However moving forward, there will be a need to be more diligent in creating lean organisations. Successful transformation will require changes throughout the entire organisation. The future business model will utilise differential resourcing as a way to achieve efficiency and leverage technology as a way to improve effectiveness.

Blockbuster drugs, large general market sales forces, specialised tactical groups, competitive benchmarking all seek to disentangle a company from its strategic focus and direction. “Hey, we’ve been successful and it’s been working… If it aint broke, don’t fix it.” The challenge is that in a hypercompetitive marketplace, a company must continually seek to reinvent itself while ensuring that they are committed to the strategic intent.

Companies should be reminded that the fundamentals of competitive advantage rest on the ability to construct a meaningful and defendable competitive position. Assuming that a well-articulated vision has been communicated from the top-down, the only way to get to this position is through a strong and unrelenting strategy.

Treacy and Wiersema in their seminal work state that a company must be disciplined in their strategic choice to focus on operational excellence (e.g. Wal-Mart), product leadership (e.g. Sony), or customer intimacy (e.g. Ritz-Carlton Hotels). Their fundamental posit rests on the fact that an organisation must meet the industry standards on two of the three distinct dimensions and differentiate on the third. Wal-Mart whose slogan is “Always Low Prices” can’t support the same structure that also brings overwhelming customer service like the Ritz-Carlton. These are two separate organisational structures that have been established to meet very different needs of the customers.

Think of it in a more relevant way to this discussion, operational efficiency is the cheapest player in town (e.g. generics), product leadership is synonymous with innovation (e.g. biotech) and customer intimacy is having the products and services that customers are looking for (e.g. Big Pharma). Daichii-Sankyo’s acquisition of Ranbaxy is doomed to fail and is already coming under pressure by the market as individuals ponder how the creation of distinct strategies will create value. Each company must identify where their strategic focus will lie. Failure to do so will result in mixed messages and decreased company valuation.

Some of the first strategic choices that must be decided are actually more formed by the guiding vision of the organisation. These choices such as therapeutic areas (set by the company’s vision), geographic presence (e.g. emerging markets), and degree of management control (e.g. globalised, hybrid transnational) are key pre-requisites that need to be decided before even discussing the strategy of the organisation.

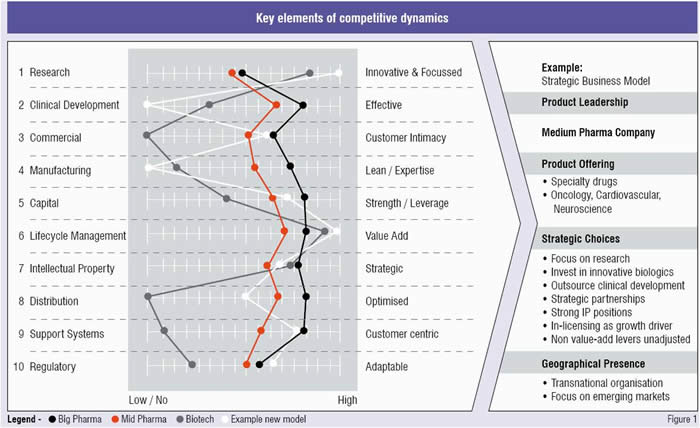

Firms need to understand where they intend to compete on the value chain from development through to commercialisation, and pull those respective competitive levers (See Figure 1). There is no magic bullet when it comes to picking which distinct strategic approach is correct. The point is a unified and fundamental decision needs to be taken —one that is differentiated from the competitive set and then very diligently followed. It takes discipline and courage especially when the market criticises and focusses on rewarding short-sighted quarterly share growth versus long-term value creation.

Adopting a strategic business model

When deciding to change the strategic business model, companies must consider the pre-existing culture, infrastructure, controls, communication, and leadership as the prerequisites that will allow for a clear and focussed strategy that is implementable. An overarching principle needs to be stuck to in order to create uncontested space where competitors are not able to easily reproduce these results.

As can be shown from the fictitious example, one can graph the traditional levers of the value chain and determine the levers that the organisation chooses to place more or less emphasis on in relation to the other competitors (i.e. types or nearest companies). Careful consideration must be given to the interdependencies that exist between levers. In this illustrative example, a decision has been made to invest at the levels in research like a biotech does while outsourcing the clinical development and manufacturing. This frees up capital to allow the organisation to be more like Big Pharma and focus its resources on in-licensing new compounds and providing additional resources to drive closer customer connections in speciality. Notice though on the levers that are not manipulated the new model that the medium pharma company embraces remain fairly similar. The sound is not optimised by an equaliser when all levers are up or down, it is the mix of the levers as it relates to the signal (i.e. market) that makes the output synchronised. The object of the game is to not have all the curves look alike—a vision of where the company wants to be and needs to be in place so that a strategy map can be created.

Heterogeneous or Homogenous?

The rationalisation of the business model

These trends as mentioned previously are being manifest in the marketplace today as is evidenced by the current events seen in the industry as well as discussed in the recent press. Diversification companies like Abbott, Solvay, and Bayer are conglomerates that have sought to balance the higher risk of pharmaceuticals with the lower risk of other businesses like agriculture, consumer, and chemicals. These types of companies currently have higher PE ratios. Investors have largely been unimpressed though. Instead of selecting a single company for their portfolios, the investors more often look to balance portfolio risk on their own with both high risk and low risk companies.

Focussed companies, on the other hand, are choosing to slough off many of their traditional core businesses in favour of reinvesting cash back into R&D to fund innovation. The rationale is that they can reap benefits through the development cycle with higher sales, earnings and ultimately valuations. The reality is that very rarely will the choice be so dichotomous, the rationalisation will lead to hybrid organisations that will reflect additional clarity within pharma with other related businesses (e.g. diagnostics, chemicals). This approach allows the most flexibility for existing diversified companies to innovate, yet keep to their strategy and culture. Although flexible, the hybrid approach may not be as competitive and fit for the market.

Because of the pressures, companies are wrestling with various means to enhance individual product lifecycle management, profitability and the health of the company. As a consequence, companies are being forced to rationalise their business model. It is clear that the questions like the following are being carefully considered:

Should the company specialise?

BMS, Pfizer, and Wyeth have been recent examples of pharma giants that have announced that they will be exiting traditional therapeutic areas (e.g., Women’s Health, Cardiovascular). Pfizer most recently announced that they will be segmenting and reorganising into three business units (primary care, speciality and emerging markets).

Maybe biologics are the answer?

The traditional pharma business model has come under fire and is being redefined as evidenced by pharma trying to buy up smaller biotech companies as they look to large molecules for innovation. Recent

examples include BMS / ImClone, Roche / Genentech, and speculation that GSK will acquire Genmab. Biologics are expected to be responsible for driving growth through 2012.

Should areas be de-prioritised?

Bristol-Myers Squibb has also announced a restructuring plan to cut its workforce by 10 per cent, close half of its manufacturing plants and move production to Asia and Latin America. Novartis has been forced to rationalise itself and has restructured in order to reduce the number of management levels, decrease bureaucracy, as well as reexamine the use of external companies to conduct drug testing. They may even close a manufacturing or research site.

What about shifting resources to focus on different parts of the value chain?

On the research and development side, companies are now looking at more effective strategies. Eli Lilly recently sold its early stage discovery and development. They have embraced the outsourcing model—40 per cent of information technology, 20 per cent of manufacturing, and 20 per cent of

sales force.

Can personalised medicine be the answer?

Solvay Pharmaceuticals is also reacting to the changing marketplace. With the sustained commitment to “Inspire 2010” to focus on profitable growth, portfolio focus, and efficiency improvements, Solvay has decreased its commercial footprint, divested non-strategic assets, increased outsourcing, and divested manufacturing sites. Moreover, in the “Transformation 2015” plan, the acquisition of Innogenetics comes more into strategic focus as biomarkers are expected to play a greater role in personalised medicine.

Is therapeutic segmentation the solution?

Recent companies like Pfizer and Wyeth (among numerous others) have announced that they will trim down their focus. In light of future patent expirations, the expectation is that the organisation can’t support as many therapeutic areas and programmes due to projected decreased ability to fund R&D. Moreover, focussing on delivering innovative and differentiated products tailored to speciality physicians should result in higher profits for the companies. Traditionally, drugs that are tailored to the larger primary care prescriber tended to be the blockbusters; generally, promotionally-intensive types have become genericised and tougher for reimbursement.

Should therapeutics and diagnostics be combined?

Although the idea of this combination has been around for some time with companies like Roche, the application is really in its infancy. Vanda Pharmaceuticals is a recent example of a company trying to combine their antipsychotic and a commercially available test to detect relevant efficacy biomarkers. Although the FDA rejected Vanda’s bid for approval for Iloperidone, the need for biomarkers and a commercially available test to predict response is clear. The question is: Are the two intertwined? Will diagnostics be adopted by healthcare providers? Will the bundling of the diagnostic to the therapeutic be adopted by healthcare providers?

References

1. SCRIP – World Pharmaceutical News, 18 Mar 2008, Informa UK Ltd.

2. “Opportunity knocks for Big Pharma as credit crunch takes ever stronger hold” Pharma Marketletter, October 20, 2008

3. Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research http://www.fda.gov/cder/rdmt/default.htm

4. Datamonitor, PharmaVitae Company Compartor Tool, September 2007, IMHC0080

5. Eli-Lilly Presentation on Chorus; Pharmaceutical Strategic Alliances, September 26, 2007

6. “Pharma’s Strategic Divide: Focus or Diversify” INVIVO: The Business & Medicine Report; September 2008

7. “Key decision-makers will shape the biosimilars market, says Datamonitor” Pharma Marketletter, October 6, 2008

8. “Biomarkers for Psychiatric Drugs: Outlier of Opportunity?” IN VIVO: The Business & Medicine Report; July/August 2008.

9. “Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors” Michael Porter; The Free Press, 1980.

10. “The Discipline of Market Leaders” Tracey & Wiersma, Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1995.