The basic structure of brand strategy evolved decades ago and has barely changed since. Its key components-clinical indication, advantages and communication methods-are relics of a time when professionals prescribed on the basis of clinical claims and little else mattered. But as our market has evolved into one where payers and patients shape decisions, the nature of brand strategy has adapted to that new environment. In this article, I describe the newly emerging characteristics of brand strategy and how it can guide your own strategic planning.

Imagine being a fly on the wall when I conduct one of my research interviews in a pharmaceutical, medtech or diagnostic company. Observe what happens when I ask one of my carefully worded questions: Please describe your brand strategy? Since I research across many countries and disease areas, the answers vary in detail. But witness enough interviews and you would notice that the typical reply conforms to a formula: The indication, followed by the claims and then the tactics for communicating those two things. Step back from the detail and you would see that that this is the implicit industry recipe for brand strategy. It is remarkable that this formula is shared across the industry, whatever the product or market, but it is even more astonishing that this formula has persisted for decades. Forty years ago, during my induction process as a very young research chemist, I recall a brand manager reciting the same thing.

That the form of a brand strategy has remained constant for decades is puzzling for a management scientist like me, who uses evolutionary science to understand our industry. Since I was that young man, technology has leapt forward in both biology and information science. Sociologically, globalisation, demographics and other trends have been inexorable. Surely, the nature of brand strategy should evolve to adapt to this very different world? And yet my research interviews mostly suggest that brand strategy is stuck in the 1970s, an era when I wore flared trousers and listened to Abba on my AM radio.

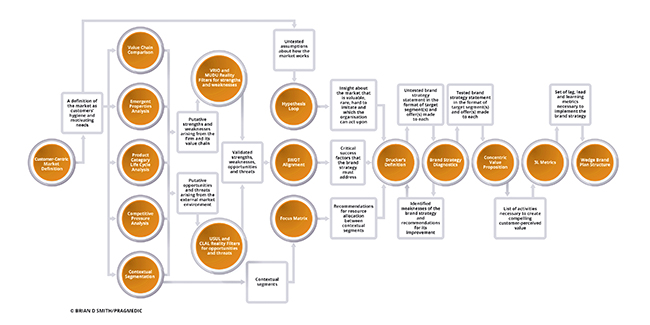

But only mostly and not entirely. In a small minority of interviews, I uncover evolutionary change in the way that brand strategy is defined and created. Its emergence is uneven and erratic, but it is there. And, in those adaptations, we see the future of brand strategy. As I describe in my book “Brand Therapy”, my research identifies no less than 15 such evolutionary adaptations (see figure) and in this article I’ll describe some of them.

The first and most fundamental adaption is the way that brand leaders define their market. Traditionally, this was done in terms of product (e.g. the statin market) or clinical condition (e.g. the hyperlipidaemia market). But modern marketers have come to realise that these definitions hinder insightful understanding of the market. After all, it is people who purchase, prescribe and consume. Neither lipids nor statins place orders. More evolved brand planning processes therefore begin with a customer-centric market definition: What is the fundamental need to be addressed (e.g. avoidance of cardiovascular disease), who is involved (e.g. prescribers, payers and patients) and what are their needs? The answer to this last question has two parts as it includes both hygiene needs (e.g. regulatory approval) and differentiating needs (e.g. for health economic evidence). This market definition, an adaptation to the changes in how choices are made and by whom, provides a much better framework for any subsequent analysis of the market.

A second adaption to changing markets is the way that market segmentation is done. Industry convention has been to divide the market by product category (e.g. mode of action) or sometimes disease stage (e.g. first vs second line). But this approach doesn’t fully address the heterogeneity of customer needs, which vary both clinically and in other ways. As a result, this simplistic categorisation leads to poor targeting and proposition design. In response to this issue, we see the emergence of contextual segmentation. This involves the segmentation of each decision maker group (e.g. prescribers, payers and patients) according to their differentiating needs (e.g. for reassurance, for value or simple posology). These three analyses then combine to allow the identification of segments made up of decision contexts characterised by the same needs and therefore behaviours. These segments form the basis for effective targeting and proposition design.

Flowing from the adoption of contextual segmentation is the emergence of a third adaptation of brand strategy: the concentric value proposition. Whereas, historically, the value proposition was almost synonymous to the product claims approved by regulatory, the concentric value proposition goes much further. It involves identifying the entire set of needs of the target segment: Core (e.g. efficacy) Extended (e.g. Information that enables product use) and Augmented (e.g. Feelings of confidence). Those needs are then translated into an integrated set of company activities that meet those needs (e.g. product claims, beyond-the-product services and CME programmes). The concentric value proposition is an adaption to the pressure from generics and the costs of developing strongly differentiated products. Unless a product is exceptional, its claims alone no longer represent sufficient value in today’s market.

Contextual segments and concentric value propositions combine to create a fourth important adaptation of brand strategy. Whilst formerly the brand strategy was implied from (and often lost in) the mass of detail in a brand plan, modern marketers have learned that this hinders execution. As a response, we see the emergence of very explicit brand strategies stated in three parts: the allocation of effort between contextual segments, the value proposition made to each targeted segment and, importantly, a specific statement of which segments will not be targeted. This clarity, which in my work I call “Drucker’s Definition” after the great management guru Peter Drucker, makes it much easier to translate strategy into action and reduces the threat of implementers going ‘off strategy’. It is, therefore, a response to tighter marketing budgets and stiffer compliance controls.

Perhaps the most radical adaption I observe in my work is that which happens between defining the brand strategy and its execution. The accepted process has been for the chosen strategy to be ‘socialised’, meaning it was discussed and tweaked until everyone in the team felt it was acceptable. This social alignment approach is now seen to be ineffective, resulting in the political dilution of the strategy until what remains is a set of choices that is agreed but which are obvious and do not create competitive advantage. What has evolved to replace socialisation is a rigorous process of brand strategy diagnostics, in which the strategy is tested against a number of transparent criteria. Those criteria, such as how well the strategy anticipates the future and how well it mitigates direct competition, are assessed using risk scales structured not unlike those used for diabetes management or to assess risk of cardiovascular disease. They allow the identification of weaknesses in the brand strategy. This in turn guides the reiteration of the brand strategy process until it an objectively strong strategy emerges. A further advantage of the diagnostic tests is that, by being transparent, the diagnostic tests enable effective ideasharing within cross-functional teams. This is much more efficient than the all too common alternative of politicised, subjectively based arguments that occur otherwise.

Many other adaptations of brand strategy in life sciences emerge from my work. These are summarised in figure shown. As the figure shows, these techniques connect together to create brand strategies that are stronger and a better fit for today’s competitive markets.

Effective brand strategy processes culminate in the final adaptation; the wedge brand plan structure. Most readers will be familiar with the typical brand plan, consisting of hundreds of pages of detail that, whatever its merits as a data collation tool, fails completely to communicate the strategy to those who must implement it. Such tomes consume time and hinder implementation. In the most advanced companies, however, we see a different structure emerging. The plan document itself is very short, containing only the essentials of the situation, strategy and activity plans. This short readable document is, however, heavily cross referenced to a large number of appendices covering market analysis, budgets, activity programmes and so on. This short document with appendices – the so-called wedge structure – is a much more effective communication document without losing any necessary details. It is a necessary adaptation to today’s time-poor work environment.

It is sobering to think of the changes in the life sciences market since I first entered the industry. It is thought-provoking to reflect that the brand strategy process in many companies has not adapted well to those changes. In those less-evolved companies, brand strategy has the same process and format as it had before the average brand manager was born. But, as is the way with evolution, we can discern the emergence of brand strategy processes and formats that are more adapted to today’s market. It is up to today’s brand leaders to adopt those emerging practices.